Human behavior and the spreading of the coronavirus

If you thought that human behavior and the spreading of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19) are in no way connected, you are mistaken.

The coronavirus keeps on attacking Europe, and we constantly see how with each passing day Governments take stricter measures in order to protect the citizens. This makes many of us wonder: why is the misbehavior of people forcing the Governments to make such radical decisions?

Why aren’t some people worried by the threatening predictions? We hear them all, we hear the data – so it should be easy to alter our behavior even without the involvement of the police? Right?

Yet, it somehow does not work this way. We still see older people gathering and mocking the seriousness of the situation. Young people saying they will travel because it is cheap to do so now. Why aren’t people listening to the recommendations? Why can’t they adjust and change their behavior – primarily socially isolate themselves – in order to protect themselves and the others?

Neuroscience and psychology might have the answer to these questions. I recently came across a very intriguing talk by Prof. Tali Sharot who explained why scaring people has very limited effect when we want them to change their behavior. She says:

We all share this deep-rooted idea that if you threaten people, if fear is induced, it will get them to act. It seems like a really reasonable assumption. Except, science shows that warnings have very limited impact on behavior.

Techniques that people use when hearing threats or when being scared

Thus, opposed to this not-so-silly idea that threats will change our behavior, what we are constantly seeing is quite a different response among people. Take smoking, exercising, or climate change for example. We all know that smoking is bad; exercising is needed; and climate change will very likely have devastating effects on our eco-system. Yet, smokers do not quit smoking even after seeing disturbing pictures on the cigarette packages that predict future health problems; non-fit people do not start exercising even though they know that in the future this can cause serious health problems; and many decide to say that “the worst case scenario of climate change might as well not happen because no one can predict the future”. Similarly, many people and countries underestimated the warning for the coronavirus and did not act on time either.

1. Avoiding negative information

Therefore, we ignore the problem and delay the action to a point where it might be as well be too late. In the case of the coronavirus, we saw this very clearly. At the start, everyone in Europe was not particularly worried, because this was something that was happening in China. Therefore, it was too far. Yet, the numbers in China were clearly showing how fast this virus spreads and how easily it can get out of control.

Europe had almost two months to prepare; yet, it ignored the problem of the coronavirus to a point when it spread so much that it was no longer possible to be ignored. This means, the warning signs for a potentially bad future were present, yet we always think we have time to gather more information regarding where those warning signs are leading to. And while we wait and “gather information”, we are taking the risk to reach the point when acting is just too late.

2. Rationalizing

In addition to ignoring problems and postponing actions that can lead to solutions, we also very commonly use rationalizations as a technique to avoid negative information. For example: “I am young and healthy, so it does not matter if I get the coronavirus. I will survive”. Or, University drop-outs rationalize like: “Steve Jobs left University and built an empire, so I will be just fine”, forgetting that Steve Jobs worked like crazy afterwards to develop his ideas and that many other University-dropouts struggle to get by.

Which information gets registered by people?

Motivated by the almost-negligible effect that threats have on people, Prof. Sharot and her team decided to investigate which information actually gets registered by people.

They conducted a social experiment in which they asked people to rate how likely is that they will face a negative outcome in the future. For example, you are asked “how likely are you to suffer a hearing loss in the future” and you give a percentage (I am 50% likely to suffer a hearing loss in the future).

Prof. Sharot’s team then engaged two experts. One of them gave the participants a better prediction (for example, you are 30% likely to suffer a hearing loss in the future); and the other one gave the participants a worse prediction (for example, you are 70% likely to suffer a hearing loss in the future). The end result was that people did not stick to their initial belief; rather, they started to believ the better version of the future. College students were the main participants in this experiment, but later people in the range from 10 to 80 years of age also engaged and the results were the same.

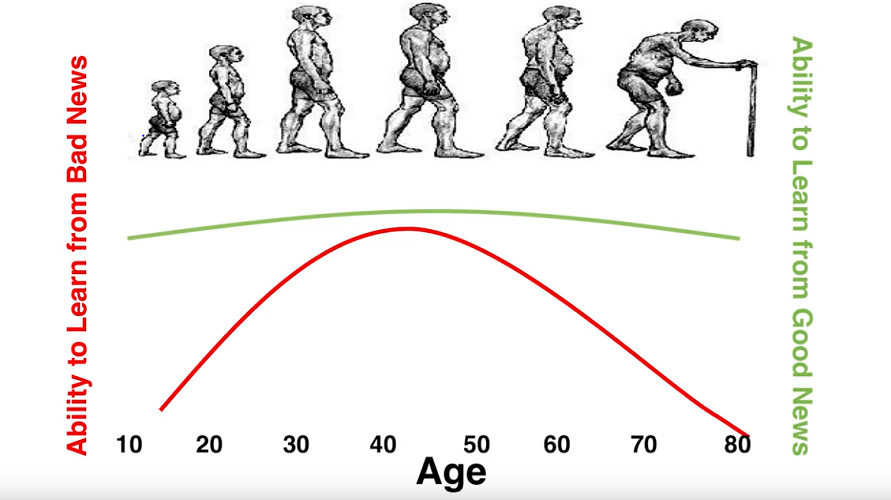

In conclusion, people take in the information they want to hear, better than the negative information. Therefore, our ability to learn from good news is much, much better than our ability to learn from bad news.

How good are we in learning from bad news?

This raises the following question: if we see among all ages that people learn better from – or filter – the good news, then how good are we actually in learning from bad news? Prof. Sharot and her team found a very interesting result: this ability changes with age. Kids, teenagers and the elderly are the worst in learning from warnings.

This makes sense, if you think about it. When you tell your kid “do not touch this glass because you will break it and hurt yourself”, they almost never listen to you. In the case of the coronavirus, the elderly people are very often taking walks and gather with friends, even though they hear the warnings that the coronavirus is especially dangerous for them! And funnily enough, the more we try to tell them that it will get worse – the least it works.

How do we motivate people to change their behavior?

If data, scaring people, and threatening them does not work, then what motivates people to change their behavior? Prof. Sharot offers three core ideas:

- Social incentives – because we care what other people do

- Immediate rewards – because we tend to choose a safe present, rather than an uncertain future

- Progress monitoring – because highlighting the progress motivates people to maintain their good behavior

1. Social incentive

We are – no doubt – social species. We care what other people do and we care what other people think of us. Thus, highlighting what other people are doing, other than just highlighting the needed action or the possible bad outcome, is an excellent way to motivate other people to change their behavior.

For example, instead of just saying “it is good to socially isolate and wash your hands in order to fight the exponential spread of the coronavirus”, one can try saying “all of my friends are socially isolating and washing their hands in order to prevent the spreading of the coronavirus”.

If you think this is silly, this technique has actually been put into practice. According to Prof. Sharot, the British Government used this principle to motivate people to pay their taxes on time. At first, the Government sent a letter to everyone who did not pay their taxes and stated how important it was to do so. Yet, none of those who evaded the payment, paid the taxes after receiving the letter. Then, the Government added only one sentence in their letter. They said: “nine out of ten people in Britain pay their taxes on time”. Apparently, this sentence enhanced compliance by 15%, resulting in 5.6 billion pounds income for the British Government.

2. Immediate Rewards

This is not at all illogical. We all tend to settle for immediate rewards, rather than future awards. We would rather have a chocolate now, rather than a possible, uncertain weight loss in the future. Young people would rather go to the bar now, than stay at home only because there is a possibility that they will get the coronavirus in the future. Thus, we choose something certain now, rather than something uncertain later, even when we know that not settling for the immediate reward will most likely lead to a positive benefit for us in the future.

However, if we reward people for doing actions now that are good for them in the future, we can bridge the temporal gap. This means, with time, we will start to associate the action we are doing now with a reward and along the way, we will convert this action to a habit.

If you think about this, we all have had an experience with immediate rewards in one way or another. For example, as students, we have chosen to take a walk in the sun, even though we knew that we will be later pulling an all-nighter to finish an assignment.

Thus, we can think how we can reward those around us who fail to comply with the recommendations from the World Health Organization during these difficult times. Every time when we do that, we are increasing the chances of them to adjust their behavior accordingly. Slow down the spread of the coronavirus. Save lives.

3. Progress Monitoring

This one is especially interesting. By now, we understood that people react to positive information much better than to negative. Thus, when we receive information about the progress we have made, not the decline, we are more likely to keep doing a good job.

For example, instead of telling people what would happen if they keep on going out during a pandemic, one can say: “in the places where people started social distancing early enough, they slowed down the spreading of the virus and enabled their healthcare system to help those people in need. Their death rate is therefore much lower”.

This is much more effective than saying “if you do not socially isolate yourself, people will die”. It is too terrifying for too many people. Therefore – we go to the start of this article – people start to ignore this information and then rationalize how there is no way that they will get the virus and spread it further around.

Wrap-up

- Scaring and threatening people with possible terrifying future scenarios makes them rather inactive.

- Regardless of age, people process positive information much better and choose to either ignore the negative information or rationalize about it.

- There are three powerful techniques that drive our mind and behavior and that can be used to motivate people to change their behavior: social incentives, immediate rewards, and progress monitoring. We observe these on an everyday basis all the time, so we might just as well use them for more serious matters.

Finally, do you have any thoughts? Did you find this article interesting or thought-provoking? Make sure to check out Prof. Sharon’s TEDx talk.

Until our next read: stay healthy!

3 Comments

Antonia

Well explained. It is really good to know something about the social science of behavior…

Ivona Kafedjiska

Thank you Dr. Rötger. I am glad you found this article informative and interesting.

Pingback: