Lise Meitner: yes to nuclear fission, no to an atomic bomb!

Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity. This is the inscription of Lise Meitner’s headstone and quite rightfully so. I am not sure if any other Physicist showed more dedication and humanity while searching for the ultimate truth than Meitner; yet, despite 19 nominations for the Nobel Prize in chemistry, and 29 nominations for the Nobel Prize in physics, for many people Meitner still remains an unknown name!

What makes Lise Meitner especially prominent and inspiring physicist in my eyes is not only her brilliant mind; the World of physics has seen many of those. Instead, is her integrity, her accountability and her scientific ethics. Unlike some of her colleagues, Meitner was incredibly forward-looking physicist when it came down to the long-term consequences of her discoveries and work.

To understand why this is so important, you have to also understand how the world and the world of physics looked like during Meitner’s most productive years.

Meitner made her most significant discoveries during the first half of the 20th century. Physics – unlike humanity, which was shaken by the horrors of two world wars – bloomed in these years! You do not really have to be a physicist to know names like Ludwig Boltzmann, Niels Bohr, Max Planck, or Albert Einstein.

Only a generation before, physicists thought that “physics was nearly complete, it seemed; its treatment of energy, motion, radiation, electromagnetism so brilliantly perfect that nothing worthwhile seemed left to discover.”

And then, discovery after discovery showed us a whole new world! X-rays, atomic spectra, sub-atomic particles, and radioactive decays were only the start. Soon, most of modern physics – especially quantum physics and the theory of relativity which shape our understanding of the world nowadays – were making physics shine more than ever.

The twentieth century: the golden era for physics, the rotted era for humanity

Naturally, these discoveries paved the road for the golden era of physics. But, hand in hand with all the curiosity and scientific thrill, came the competition. And even more so, the Nazis and those opposing them increased the pressure on physicists. Everyone wanted the geniuses of the time to be on their side and to give valuable input into all possible military actions.

Therefore, the twentieth-century physicists were simultaneously blessed and cursed. They had the immense luck to live through some of the most exciting years that physics has seen; and yet, they were also incredibly unfortunate. Physics was no longer an independent scientific branch that simply focused on asking and answering intriguing questions; instead, it has become the “man behind the curtain” which could have made the whole difference between who lives and who dies; who wins and who looses.

This is why the emotional intelligence, the humanity, the forward thinking of the physicist at the time were just as equally important as the intellectual ability to come up with ingenious ideas and theories. This was especially true for those who worked in nuclear or quantum physics. They had to choose if they would or would not work on nuclear weapons, and in particular, on the nuclear bomb.

Making choices: to bomb or not to bomb, that is the question

Everyone had a choice and everyone made that choice. Some – like Werner Heisenberg for example – sided with the Nazis. Despite his brilliant mind and outstanding discoveries in quantum mechanics, Heisenberg was the principle scientist in the German nuclear weapons program during World War II.

Others – like Lise Meitner – fled Germany. As the mind who explained nuclear fission, she had the opportunity to join the Manhattan project – the very same project that created the nuclear bomb. Instead, she loudly declared:

I will have nothing to do with a bomb!

One might think that Lise Meitner said this because she was born Jewish; but, the truth is that any involvement with the bomb was against Meitner’s core moral and ethical values. In one occasion, way before the start of the war, she has said:

What distresses me most is the frightful egotism of my current way of life. Everything I do benefits only me, my ambition and my pleasure in scientific work. It seems I have chosen a path which flies in the face of my most deeply held principle, that everyone should be there for others.

By that I don’t mean one must sacrifice oneself for no reason, but that somehow our lives should be connected with others, should be necessary for others. I, however, am free as a bird, because I am of use to no one. Perhaps that is the worst loneliness of all.

Yet, despite all of this, some still call Meitner “the Jew mother of the atomic bomb”. With this sentence, we are betraying Meitner’s legacy of a highly-ethical and humane scientist. I think, to Meitner, this would have felt even a bigger of an injustice than not awarding her the Nobel Prize for her contribution to the discovery of nuclear fission.

Lise Meitner: personal profile

Lise Meitner’s story starts in 1901 at the University of Vienna. By 1905 she became the second woman at the University of Vienna to earn a doctoral degree in physics.

In Vienna, Boltzmann taught most of her classes and he inspired Meitner to a great extent. In many ways, Boltzmann became a mentor for Lise Meitner in more ways than one. Thanks to him, she understood physics to be a passionate commitment of intellect, strength, and integrity; something that Meitner’s nephew Otto Robert Frisch confirmed when he wrote: “Boltzmann gave her the vision of physics as a battle for ultimate truth, a vision she never lost.”

After completing her doctoral degree, Stefan Meyer introduced Meitner to radioactivity. Meitner focused on scattering of alpha particles – basically two protons and two neutrons bonded in one atomic nuclei (similar to a 2+ atom of Helium). She found correlation between the atomic mass (the sum of protons and neutrons in the atom) and the scattering. Namely, the higher the atomic mass, the larger the scattering.

This discovery directly motivated Ernest Rutherford to conclude that much of the atomic mass is concentrated into a tiny, dense, positively charged nucleus; while the light, negative electrons revolve around this core in very much a similar matter as the planets revolve around the sun. This is nowadays known as the Rutherford’s model of the atom; but, sadly not many know that Lise Meitner’s work set the foundation for this discovery with her work on scattering of alpha particles.

Moving and living in Berlin: Lise Meitner’s way of living the dream

Regardless of her great work in Vienna, Meitner chose to go to Berlin. There were several reasons for this. First and foremost, Berlin was a German-speaking city that Boltzmann had highly praised. But, above all, Berlin was the city where Max Planck was working. Meitner hoped that Plack would be Boltzmann’s successor.

However, women could not attend Prussian Universities at the time. It is very easy from today’s point of view to glorify Planck for finding the strength to make an exception and support Meitner to come to Berlin; but, the truth is that he had rather conservative view of women in physics as well.

-

Max Planck’s statement on women in physics (1987):

If a woman possesses a special gift for the tasks of theoretical physics and also the drive to develop her talent, which does not happen often, but does happen on occasion, then I consider it unjust, from a personal as well as an objective point of view, to categorically deny her the means to study as a matter of principle; if it is at all compatible with academic order I shall readily admit her, on a trial basis and always irrevocably, to my lectures and my practical courses…

On the other hand, I must hold fast to the idea that such a case must always be considered an exception, and in particular that it would be a great mistake to establish special institutions to induce women into academic study, at least not into pure scientific research. Amazons are abnormal, even in intellectual fields. In certain practical situations, for example, women’s health care, conditions might be different; but, in general, it can not be emphasized strongly enough that Nature itself has designated for woman her vocation as mother and housewife. Under no circumstances can natural laws be ignored without grave damage, which in this case would appear especially in the next generation.

Even though it is sad to read that as brilliant mind as Planck’s could have thought this, it is a relief to know that he considered Meitner to be exactly one of those “rare exceptions”. The fact that he granted her the permission to attend his lectures speaks loudly of how competent she was.

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn – early years of research

However, Meitner soon realized that Planck’s lectures in no way would fill all of her time. Lise Meiner than made a career-defining move and approached Heinrich Rubens and asked him for a place in his laboratory. He, in return, introduced Lise to Otto Hahn – a chemist with whom she will continue working for many more years.

-

Radioactive recoil

One of the most valuable discoveries that Meitner and Hahn did in their early collaboration was on radioactive recoil. In order to understand recoiling, think of firing a gun. When the bullet leaves the gun, the gun recoils (kicks back).

Similarly, in 1909, Meitner and Hahn found that when a positively-charged atomic nucleus emits an alpha particle, it recoils. The nucleus can be collected to a negatively-charged electrode where it can produce elements with very high purity. From today’s perspective, these were not really new elements. They were isotopes – variations of one element with different number of neutrons in the nucleus.

-

231-protactinium isotope

In 1912, they paused they work because Meitner left to work as a nurse on the front-line of World War I. They continued their work in 1916 and by 1917, Meitner and Hahn discovered a new isotope of the element protactinium. Although some short-lived isotopes of this element were already known, they succeeded in discovering the 231-protactinium isotope which has a half-life of 32 000 years, allowing them to investigate and establish the element’s physical and chemical properties for the first time.

-

Career advancements

The Berlin Academy also recognized the significance of this discovery and granted Meitner the Leibniz medal for the protactinium discovery. Soon after this, her reputation grew significantly.

In 1918 she became the Director of Radiation Physics. By 1922 she was the first one to observe so-called radiationless transitions. In these transitions, energy is firstly transferred to an electron; and afterwards, the electron leaves the atom. However, this discovery today is knows as the “Auger effect“, even though Pierre Victor Auger independently discovered this phenomenon one year after Lise Meitner.

By 1926, she became the first female professor of physics in Germany.

Lise Meitner, Otto Hahn, the 1930s, nuclear fission, and the fall apart of a years-long friendship and collaboration

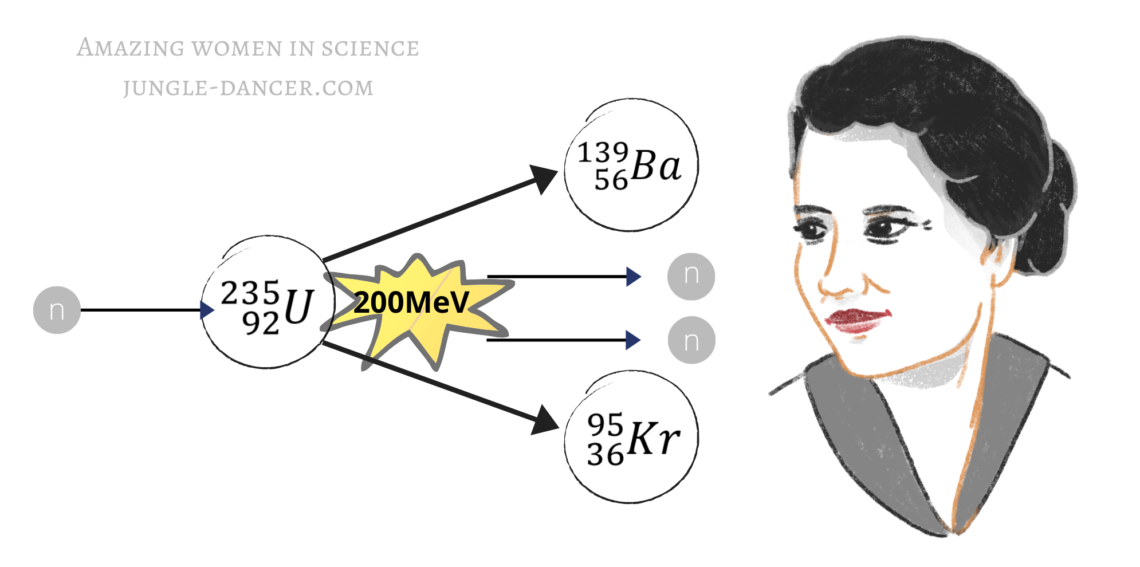

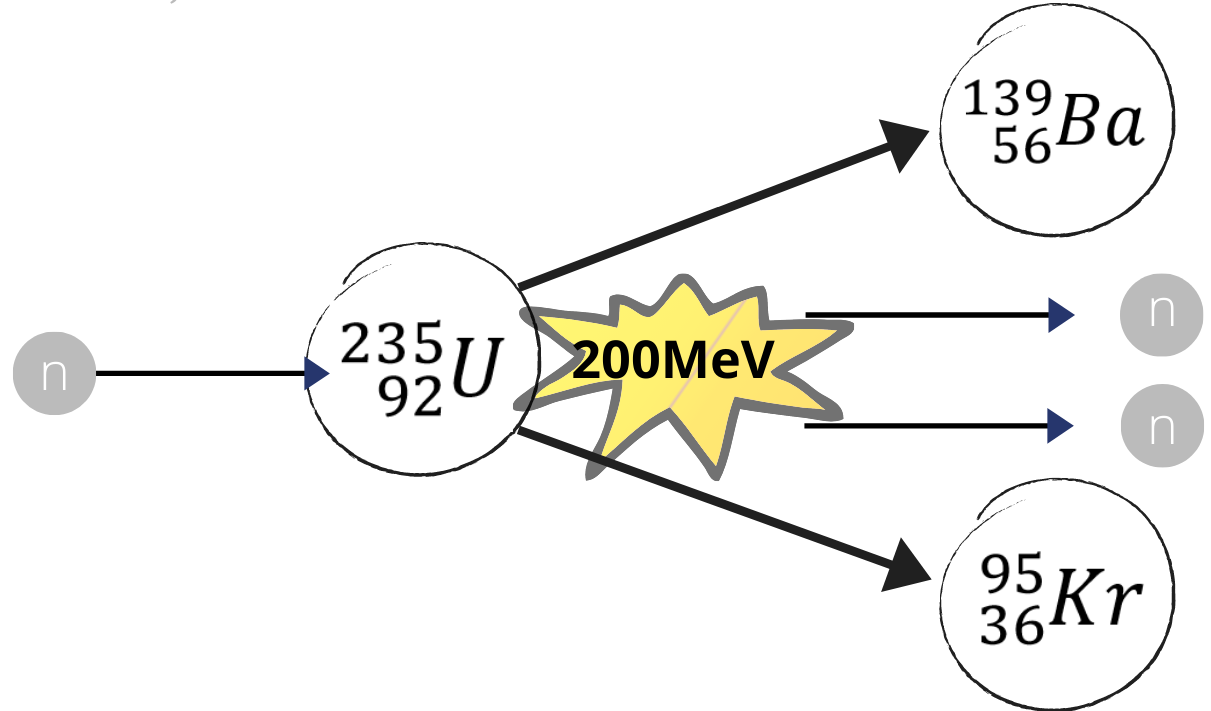

Enrico Fermi set the foundations of nuclear fission with his work on bombarding 92-uranium with neutron. Here 92 represents the number of protons in the atomic nucleus. Through this process, uranium gained a proton and formed element 93. At the time, as far as our knowledge went, uranium was the heaviest element. Thus, Fermi suggested that scientists could use this method to make heavier elements than uranium. He called these elements transuranic elements.

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn quickly started investigating these transuranic elements. Sadly, they spent four years (1934 – 1938) of their carrier, only to reach wrong conclusions. By July 1938, Lise Meitner had to escape to Sweden. It was a matter of life and death, since the conditions for Jewish people under Hitler’s rule were worsening. Sadly, she was not present when soon afterwards, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman performed the experiments that forever changed the world as we know it.

The two of them bombarded uranium with slow-moving neutrons and collected data that indicated that uranium was producing barium. The problem was, uranium has an atomic number of 92, while barium has an atomic number of 56. The difference in the atomic number was simply too large, which led Hahn to write to Lise Meitner that “they [Hahn and Strassman] themselves realize that uranium cannot really break into barium”.

But, in reality, through nuclear fission, it can! Nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which a nucleus of an atom splits into two smaller nuclei and in this process, releases a large amount of energy.

Lise Meitner solving the puzzle

Lise Meitner came up with the solution to the puzzle during a long walk in the woods. She estimated that under the condition there is a small disturbance of the nucleus of a radioactive element, this nucleus can break into two other, almost equally-sized, nuclei. Einstein’s famous formula E = mc2 inspired Meitner. She also made a quick calculation and estimated the amount of energy that will be released in such a process (~ 200MeV).

Meitner and her nephew Otto Frish submitted a paper to Nature. Sadly this paper saw the light of day in February 1939; only one month after Hahn and Strassmann published their detection of barium. They excluded Meitner from the authors’ list, even though she herself wrote to Hahn to explain him how – despite Hahn’s disbelief – the production of barium is actually quite possible.

Another scientist who knew of Lise Meitner’s theoretical/analytical explanation of nuclear fission was Niels Bohr. He simultaneously carried the news to the USA and fought for recognition for Meitner. However, despite Bohr’s efforts, only Otto Hahn received the 1944 Nobel Prize in chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission.

Otto Hahn negating Lise Meitner’s contribution to the discovery of nuclear fission

Meitner felt simultaneously betrayed both by the scientific community and her friend. Even though Hahn gave Meitner credit in his Nobel Prize speech, he initially had downplayed her role. Meitner taught that because she fled Nazi Germany illegally, he feared to associate his name with hers. However, when he continued to downplay her scientific significance even after the war, Meitner no longer justified his behavior.

In fact, for the rest of his life Hahn stuck to the following explanation: “fission was a discovery that relied on chemistry only and took place after Meitner left Berlin; she and physics had nothing to do with it, except to prevent it from happening sooner.”

Strassmann, on the other hand, believed Lise Meitner to be the intellectual leader of their team. Finally, Meitner herself, never really said anything publicly in her defense. Instead, she kept on underlying the important interplay of physics and chemistry in their research. In private, however, she said that “Hahn has supressed the past and that she is part of that suppressed past.”

It is nowadays know that Hahn himself did not really believe that uranium could decay to barium; it was only after Meitner’s letter and explanation that he had found the courage to prepare a publication.

Was Meitner naive for sharing her findings so quickly, eagerly, and promptly? Maybe. But, here we have two people who – she believed – were friends for decades. She could have never imagined that Hahn would later negate her contribution to the work. Her high morals and trust in people simply did not allow her to imagine this to be possible.

Lise Meitner and our society negating her role in the discovery of nuclear fission; yet, calling her “the Jew mother of the atomic bomb”

Yet, beyond the personal injustice that Otto Hahn inflicted upon Meitner; we are nowadays also facing the aftermath of our false twists of Lise Meinter’s work and integrity.

Here is the irony: by not awarding her the Nobel Prize for the discovery of nuclear fission, we have negated Meitner’s truthful explanation of what actually happens during nuclear fission. Yet, we point our finger towards her when it comes to the “inventor” of the atomic bomb.

Lise Meitner despised everything that had to do with the bomb; but, above it all, she despised and blamed all of those scientists who simply did not care about the consequences of their actions. As a food for thought, I want to finish with one letter that Meitner wrote to Hahn. He never received the letter; nevertheless, I think her words speak more loudly than mine ever could. Here is where she stood and what she thought of the war and of the involvement of the scientists in it.

The letter that Otto Hahn never received

In June 1945, as shown in Sime’s book “Lise Meitner: a life in physics“, she wrote to Hahn:

You all worked for Nazi Germany. And you did not even try passive resistance. Granted, to absolve your conscience, you helped some oppressed person here and there; but, millions of innocent human beings were murdered and there was no protest.

Here in neutral Sweden, long before the end of the war, there was discussion of what should be done with German scholars once the war is over. I and many others are of the opinion that the one path for you would be to deliver an open statement that you are aware that through your passivity you share responsibility for what has happened, and that you have the need to work for what can be done to make amends.

But many think it is too late for that. These people say that first you betrayed your friends; then your men and your children when you let them stake their lives on a criminal war; and finally, that you betrayed Germany itself, because when the war was already quite hopeless, you never once spoke out against the meaningless destruction of Germany.

That sounds pitiless; nevertheless, I believe that the reason that the reason I write this to you is true friendship. In the last few days one had heard of the unbelievably gruesome things in the concentration camps; it overwhelms everything one previously feared. When I heard on English radio a very detailed report by the English and Americans about Belsen and Buchenwald, I began to cry out loud and lay awake all night. And if you had seen those people who were brought here from the camps. One should take a man like Heisenberg and millions like him, and force them to look at these camps and the martyred people…

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Lorna Schütte for her illustration of Lise Meitner. Make sure you follow her creative work on instagram. Also, we did a similar collaboration on Jane Goodall – which you can find here. A few more posts on awesome women in science will follow.

Many of the quotes in this text are retrieved from the book “Lise Meitner: a life in physics“ by Ruth Lewin Sime. It is a truly inspiring and beautiful book; so, if you are interested in more details about Lise Meitner’s life, this book is the way to go.

If you are interested in Lise Meitner’s Nobel Prize nominations, check out the The Nobel Prize Archive.